Swiss Info | 18 July 2024

Why Switzerland is diverging from Europe on a key energy treaty

by Luigi Jorio

The European Union will withdraw from the Energy Charter Treaty, an international agreement that protects investments in coal and oil. But Switzerland is sticking to the agreement which scientists considered incompatible with climate goals. Why is Switzerland going its own way, and what could happen next?

If you have never heard of it, you’re not alone. The Energy Charter Treaty (ECT) is not well known to the public. But it has major consequences for the type of energy that heats our homes and powers our electronic devices.

What is it all about?

The ECT is an agreement initiated by the European Union (EU) for cooperation in the energy sector. It contains binding provisions that protect investment and trade.

The ECT was created after the end of the Cold War with the aim of integrating the countries of the former Soviet Union into the European and global energy markets. It was signed in 1994 in Lisbon and entered into force in 1998.

Originally, it offered additional guarantees to Western companies investing in the energy resources of the former Soviet states. It protected investments in gas and oil if, for example, a government expropriated, nationalised or terminated contracts prematurely.

Which countries signed the treaty?

Almost all EU member states, the United Kingdom, Norway, Turkey, Japan and some central and west Asian countries have signed. Switzerland ratified it in 1996.

But some countries have withdrawn – as Italy did in 2016 – or have announced their intention to do so. On May 30, the EU announced that it will withdraw from the ECT by the end of the year.

Why are countries withdrawing from the treaty?

The ECT is criticised for hindering the implementation of national climate policies. The EU Council says that the treaty is no longer in line with the Paris Climate Agreement and energy transition ambitions.

Under the treaty, a company or investor group can sue a state, and claim compensation, if they believe that national policies threaten their activities and interests. For example, a company operating oil fields could take legal action against governments that adopt laws to reduce CO2 emissions.

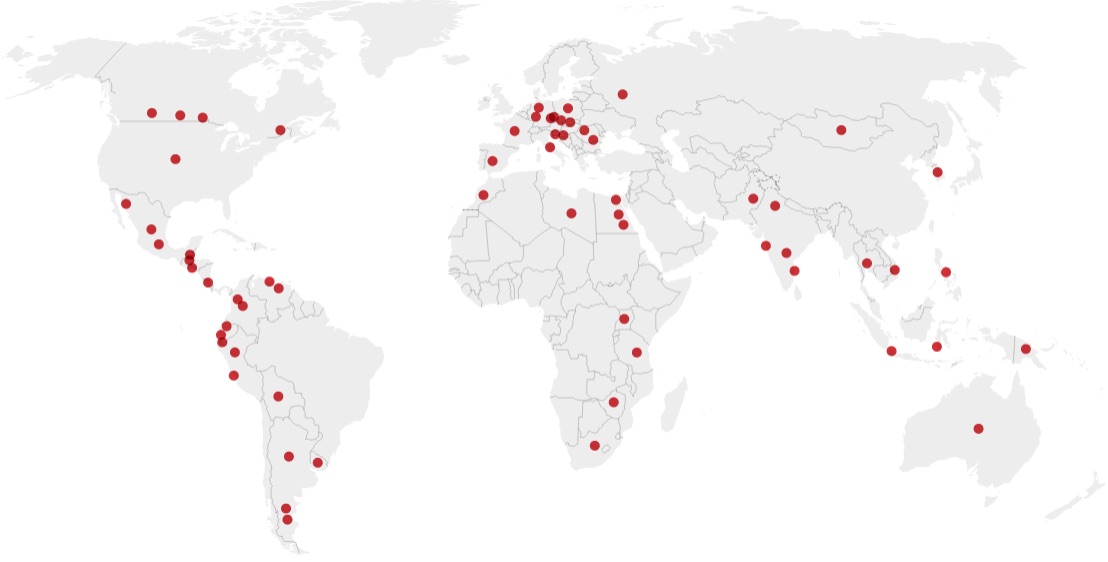

There have been more than 160 legal disputes worldwide. So far, eight Swiss investors have taken legal action against a state under the ECT. Most recently, the Azienda Elettrica Ticinese (AET), an energy provider in the southern Swiss canton of Ticino, sued the German government in 2023 in connection with its decision to abandon coal. A decade earlier, AET had invested CHF35 million ($39 million) in the coal-fired Lünen power plant in Germany’s Ruhr region.

AET’s lawsuit against Germany is “concerning for the signals that it could send to other countries that are trying to phase out coal power”, says Kyla Tienhaara, a professor of environmental studies at Queen’s University in Canada.

In view of the increasing number of legal disputes, EU countries have proposed to amend the treaty. The aim is to gradually eliminate the protection of fossil fuel investments and bring the ECT in line with the Paris Agreement. However, no compromise has been found so far, prompting several countries to leave the treaty.

Is the ECT an obstacle to energy transition?

The Swiss government, for its part, argues that the ECT does not prevent any signatory state from pursuing an ambitious climate policy.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and more than 500 climate scientists and experts do not agree. They say that the treaty’s protection of fossil energy investments is an obstacle to energy transition.

“It is crystal clear that the ECT, whether reformed or not, is incompatible with net-zero goals,” Eunjung Lee, senior policy advisor at E3G, an independent climate change think tank, tells SWI swissinfo.

The ECT is “a powerful tool in the hands of big gas, oil and coal companies to dissuade governments from making the transition to clean energies,” argues Alliance Sud, representing the major Swiss organisations active in international development.

The treaty’s mechanism for settling disputes between investors and a state is particularly controversial. It would benefit multinational companies and award them billions in compensation, according to those who criticize the ECT.

“In principle, an investor who loses money [due to emissions-reducing measures] should be able to get compensation,” says Isolda Agazzi of Alliance Sud. But the amount should be decided by a domestic court or defined by other procedures, not through private arbitration as is currently the case, she says.

What is Switzerland’s position?

In 2021, the Swiss government stated that withdrawing from the treaty would not be in the country’s interest with regards to investment protection and multilateral investment law.

But Switzerland supports modernising the ECT. Marianne Zünd, head of communications at the Swiss Federal Office of Energy (SFOE), says modernisation would significantly strengthen environmental and climate protection. The new text should mention the Paris Agreement and allow member states to unilaterally exclude fossil energies from the list of investments, she says.

By remaining in the treaty, “Switzerland is contradicting its own climate commitments and defending the outdated legal system that puts fossil fuels interests above those of the public”, according to Eunjung Lee.

Yamina Saheb, a former ECT employee and author of an IPCC report on climate change mitigation, also finds the Swiss position “incomprehensible” and “contradictory to Switzerland’s climate policies”.

What could be the consequences of Switzerland remaining in the ECT?

Alliance Sud and other non-governmental organisations fear that fossil energy companies will move their headquarters from the EU to Switzerland to remain within the scope of the treaty. This would allow them to continue to sue states that adopt climate protection policies.

“Switzerland will become a base for unscrupulous investors who would dare to use the sunset clause [of the ECT] against countries that withdraw from the treaty,” says Yamina Saheb. This clause allows a country to be prosecuted for up to 20 years after its withdrawal from the treaty.

The SFOE told SWI swissinfo.ch it does not wish to comment on such “speculation, for which there is currently no evidence”.

Switzerland expects the modernisation of the ECT to be adopted at the next Energy Charter Conference in the autumn of 2024, according to Marianne Zünd, head of the SFOE media and politics division. The federal government will then decide how to proceed, taking into account which EU member states will withdraw.