Euractiv | 10 July 2019

Nord Stream 2, EU drifting towards legal arbitration

By Georgi Gotev

The European Commission and the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline company are heading toward legal arbitration in their dispute, with a risk of huge fines for EU taxpayers and uncertainties for the Gazprom-led company that are even more difficult to evaluate.

The deadline Nord Stream 2 has given the European Commission in an attempt to settle the dispute has elapsed on 12 July.

The next step now is legal arbitration under the Energy Charter Treaty in a case that carries significant risks for both sides.

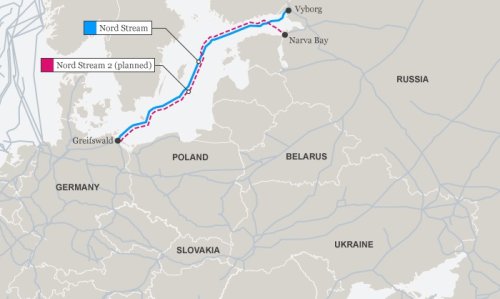

The controversial €11 billion new gas link between Russia and Germany is to run under the Baltic Sea and set to double Russian gas shipments to the EU’s largest economy.

Western European investors Engie, OMV, Shell, Uniper, Wintershall, are part of the project, which is led by Russian gas monopoly Gazprom. Germany strongly supports the project, while its main detractors are Poland and the Baltic countries.

The first Nord Stream pipeline did not raise concern at the time of its construction. On the contrary, then energy Commissioner Günther Oettinger attended its inauguration in 2011, together with German Chancellor Angela Merkel, Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte and then French Prime Minister François Fillon.

But tables have turned before the completion of the Nord Stream 2 project, aimed at doubling the capacity of the existing offshore pipeline.

Tensions grew, especially after Russia annexed the Ukrainian region of Crimea. It also became obvious that Moscow was using its gas export monopoly as a political weapon in the dispute with Ukraine over gas transit fees, raising concerns about Western Europe’s reliance on Russian gas.

The issue reached even greater geopolitical proportions after US President Donald Trump attacked Germany over Nord Stream 2 at the July 2018 NATO summit in Brussels.

The European Commission has come under pressure from Poland and the Baltic states to legislate on Nord Stream, and tabled an amendment to the EU Gas Directive in November 2017.

While the amendments – relating to third-party access, tariff regulation, ownership unbundling and transparency – aren’t officially directed against any particular project, they were obviously designed to stop Nord Stream 2.

Legal experts have recently argued that the amendment is drafted in such a way that all existing pipelines can enjoy a derogation from EU gas market rules under the updated Gas Directive, except Nord Stream 2. The derogation is indeed available for pipelines that are “completed before the date of entry into force of this Directive,” which is 23 May 2019.

According to them, the discriminatory treatment of Nord Stream 2 stems from the fact that it is the only import pipeline which cannot benefit from the derogation, because the final investment decision was made before this date, even though significant capital was committed.

Interests of Western investors at stake

The European Commission has created “discriminatory legislation” which affects not only the interests of Nord Stream 2 and its shareholder Gazprom, but also the projects of its five Western European financial investors, said Sebastian Sass, the Nord Stream 2 chief lobbyist to the EU institutions.

This was undermining the confidence of any investor in the internal energy market more broadly, Sass told EURACTIV.

“This leads to significant legal risks for the EU as a whole, including potential claims for damages under the Energy Charter Treaty.”

The Energy Charter Treaty (ECT) was initially aimed to integrate the energy sectors of the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe at the end of the Cold War into the broader European and world markets.

Settlements under the Energy Charter Treaty are sometimes in the billions of dollars. In 2014, the nearly 10-year-long Yukos case was decided in favour of the claimants on the basis of the treaty, with a record-breaking $50 billion award. Russia has in the meantime decided to pull out from the Energy Charter.

Bad law-making?

Sass said that in September 2017, the Commission had announced the amendments to the Gas Directive “like pulling a rabbit out of a hat” – without an impact assessment or public consultation.

According to him, this happened immediately after the Commission’s failed attempt to apply the Gas Directive only to Nord Stream 2, while safeguarding all other import pipelines. The attempt failed because the Commission’s own legal services, backed by the Council, had attested a lack of legal basis.

A 7-page document by law firm Herbert Smith Freehills lists in detail all the legal arguments of the Nord Stream 2 company, which have been handed to the Commission.

In short, Sass said the Commission had in effect tried to apply EU gas market rules to Nord Stream 2 differently from all other import pipelines.

“Such an approach is fundamentally problematic in view of basic legal principles such as non-discrimination,” he insisted.

Sass reminded that Nord Stream 2’s CEO raised the company’s concerns in his letter to Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker on 12 April, launching a dispute settlement procedure under the Energy Charter Treaty. A meeting with the Commission took place on 25 June with the aim to achieve an amicable settlement. A three-month period to settle the dispute amicably ended on 12 July.

Since the company’s concerns remain unresolved, the next most probable step is legal arbitration, as stated ina more recent letter of the Nord Stream 2 company to the Commission.

The risks of such an arbitration for the EU are potentially huge. Under the standard procedure, three arbiters would be designated to rule on the legal claims. Given the multi-billion cost of the project, the Commission might end up paying huge amounts of taxpayers’ money as compensation and fine. There is also a possibility that Nord Stream 2 would seize the EU Court of Justice to complain against a violation of the non-discriminatory principle enshrined into EU law.

For Nord Stream 2, the risks are of multiple nature and include, aside from the possible US sanctions, hurdles in completing the last stretch of the pipeline in Danish territorial waters.

A new European Commission and a new Vice President responsible for energy are also important factors of uncertainty.

Some member states, Poland in particular, are coveting the Energy Union portfolio of Current Vice President Maroš Šefčovič, in a bid to oppose Nord Stream 2.

Separately, a process has been launched to “modernise” the Energy Charter Treaty, a process in which Europe recently decided to assert its “right to regulate” against the interests of foreign companies.

However, any agreement to reform charter would require unanimity from all the signatories of the treaty, which has 55 members.