CCSI | January 2024

How the international investment law regime undermines access to justice for investment-affected stakeholders

by Ladan Mehranvar

For over a decade now, the international investment law regime, which includes investment

treaties and their central pillar, the investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) mechanism,

has been facing sustained calls for reform. These have largely centered on the concerns

regarding the high costs of ISDS, the restrictions placed by the investment treaty regime on

the right—or duty—of states to regulate in the public interest, and the questionable benefits

arising from these treaties in the first place. Several states have taken proactive measures:

some have revised investment treaty standards to better protect their regulatory powers;1

others have introduced new approaches to investment promotion, protection, and dispute

settlement that more closely align with their sustainable development objectives;2 and

some states have withdrawn from the investment treaty regime altogether.3 In addition,

reforms to the regime are taking place at the multilateral level within the United Nations

Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL),4 the Organization for Economic

Cooperation and Development (OECD),5 the World Trade Organization (WTO),6 and through

other regional fora.7

Despite being the subject of extensive and prolonged public debate for several years, these

reforms have continued to reinforce the binary structure of the regime. This structure

restricts the focus of investment relations solely to investors and host states, disregarding

the actual or potential impacts of investment projects, relations, disputes and awards on the

rights and interests of other impacted stakeholders. In particular, large-scale, land-based

investment projects involve a broad network of people and relations, and often intersect

with local communities whose social identity, way of life, and livelihoods are intimately

connected to the land and natural resources at stake.8 It is this category of investments,

which result in the creation of a new “project” with a large land footprint, that is the topic

of this paper. The consequences of these types of investments can be significant, as they

often lead to land expropriations, negative human health consequences, water pollution,

air contamination, deforestation, or shifts in migration patterns within the area,9 thereby

impacting the rights and interests of people in these communities and the environment

more broadly.

From the perspective of investment-affected communities,10 foreign investments arise

out of a partnership between the investor and the state.11 After all, it is the government

that facilitates the establishment and development of these very projects. Meanwhile,

these impacted people are often not consulted or involved in project establishment or

development, and many may not even know that a project has been approved until after it

has been approved or once it is operational. According to scholarship in this area,12 these

affected individuals and communities often find themselves in a situation where they must

assert their rights against the negative impacts of such projects, or resist these projects by

mobilizing, protesting, or resorting to legal (and non-legal) measures against the investor

and/or the state. This dynamic is frequently reflected in investment disputes, in which

foreign investors challenge measures that state agencies have taken in response to, inter

alia, local opposition to investments, in an attempt to safeguard their economic interests.13

However, even though the underlying investments, government measures, ISDS disputes,

and any resulting awards often implicate local people and communities in profound ways,

these stakeholders find it difficult, if not impossible, to assert their rights and have their

concerns addressed in investment policy making, in the establishment or continuation

of investment projects, and in any ensuing investor-state disputes that may arise under

investment treaties (or investment contracts). In fact, the voices of investment-affected

people are effectively, and in most cases, actually excluded from the “institutional logic” of

the investment treaty regime.14 This is because of the narrow scope of the applicable treaties

and the limited consideration given to human rights and domestic legal frameworks in ISDS

proceedings. In addition, these communities often encounter legal and practical obstacles

when seeking to protect their rights and interests under other instruments and fora, like

international human rights law, or domestic and regional judicial systems. This is because

victories won by investment-affected communities at these other fora are often pyrrhic

since they may ultimately be undermined by the investment treaty regime if or when the

investor succeeds in its ISDS claim.

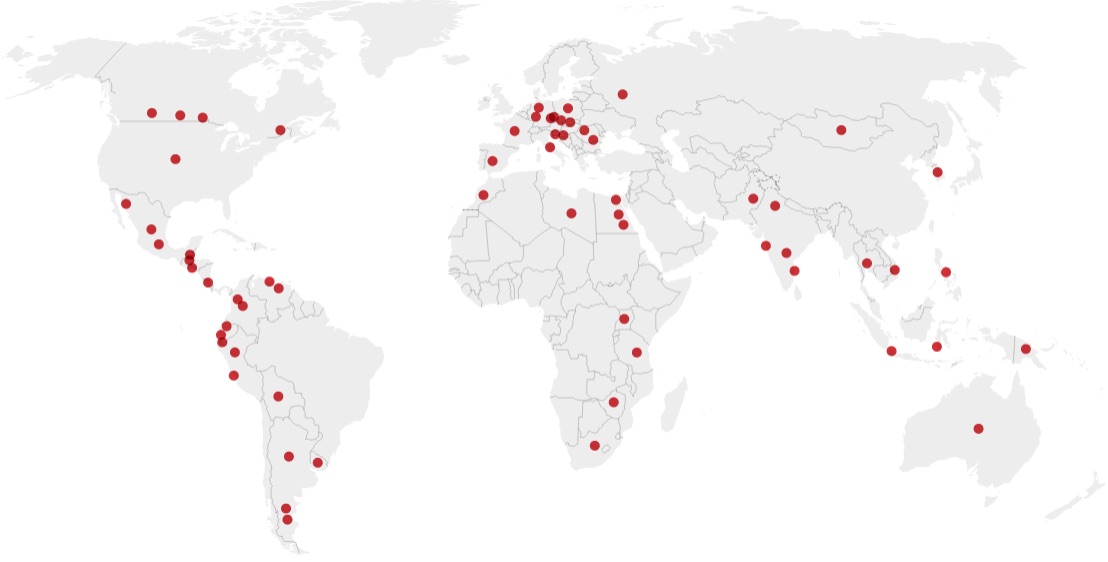

It is this local dimension, which has received little attention in public debate and action on

reform at the global, regional, and national levels, that is the focus of this paper. We draw

on a group of 13 investor-state claims (and two potential claims)15 that relate to the rights

and interests of impacted communities and identify ways in which their access to justice is

undermined, hampered or denied entirely by the ISDS mechanism.16 Before describing the

ways that access to justice is undermined or denied in these ISDS cases, we first define the

term “access to justice” below.

Read more (pdf)