National Farmers Union, Canada

CETA Investor-State Dispute Settlement process “anti-democratic, unnecessary and unfair,” says NFU

13 February 2013

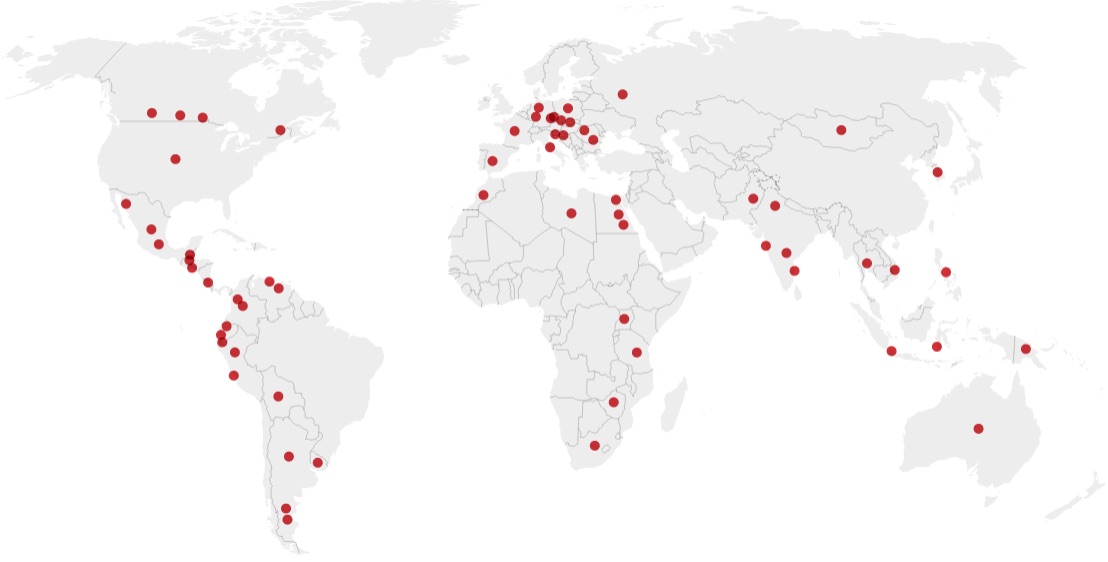

(Saskatoon) - The National Farmers Union is among the labour, environmental, Indigenous, women’s, academic, health sector and fair trade organizations representing over 65 million people from both sides of the Atlantic that have signed a joint statement demanding that Canada and the EU stop negotiating an excessive and controversial investor rights chapter in the proposed Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA).

The Transatlantic Statement Opposing Excessive Corporate Rights (Investor-State Dispute Settlement) in the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) outlines six overarching reasons for our collective opposition to this Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) process:

ISDS weakens democracy.

European and Canadian legal systems are more than capable of handling disputes between investors and governments in cases of serious wrongdoing or breach of contract.

ISDS forces taxpayers to pay for the public health, environmental and other regulations of their governments.

The CETA investment chapter ignores the lessons that Canada should have learned since NAFTA, as well as demands for balance from the European Parliament.

Investor-state arbitration is unaccountable and prone to corporate bias.

There is scant evidence that ISDS encourages inward or outward investment.

The above reasons are more fully developed in the Statement. However, they can be summed up by saying Investor-State Dispute Settlement processes are anti-democratic, unnecessary and unfair.

“The Canadian government has been negotiating CETA behind closed doors since 2009. While publicly using the language of trade, CETA is in effect a binding international contract that, if signed, will constrain the powers of elected governments by taking away substantial jurisdiction over key public responsibilities at the federal, provincial and municipal levels,” said Ann Slater, NFU Region 3 Coordinator. “It would make legitimate government power subject to the demands of transnational corporations that put their own profitability and market share above the interests of the people who live in our respective countries.”

The Investor-State Dispute Settlement process is a key method of enforcing the contract. It is a process that exists outside of our court system and is not accountable to the Canadian public. Disputes would be settled by an appointed panel, in secret, and if the corporation wins, the government would be required to pay compensation for future lost profits deemed to result from the legislation or regulation in question.

“If an Investor-State Dispute Settlement process is included in CETA, governments will certainly hesitate to take any action that could result in a dispute and subsequent fine,” said NFU President, Terry Boehm. “The population may still be able to vote, but the corporations would have the last word.”

For more information:

Ann Slater, NFU Region 3 Coordinator: Phone: (519) 349-2448 or Email: aslater@quadro.net

Terry Boehm, NFU President: Phone: 011 33 1 44 84 72 50 (Paris) or Email: centaur2@sasktel.net

See Trade Justice Network or read full text of joint statement below

Transatlantic Statement Opposing Excessive Corporate Rights (Investor-State Dispute Settlement) in the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA)

February 5, 2013

The undersigned European, Canadian and Quebec organizations strongly oppose the inclusion of an excessive investment protection chapter and investor-state dispute settlement process (ISDS) in the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) for the following reasons:

1. ISDS weakens democracy: The dispute process creates a parallel legal system that is exclusively available to foreign investors and multinational corporations. These investors increasingly invoke their excessive investor rights in bilateral investment treaties and free trade agreements to challenge legitimate, legal and non-discriminatory government measures. No other rights – human, Indigenous, ecological, etc. – are so effectively enforced. And governments have no comparable rights to hold corporations accountable for their activities. In fact, the ability to do so is undermined by ISDS and agreements such as CETA, which would live on like a zombie for 20 years, even if Canada or the EU cancelled the deal in the future. For these and other reasons, the Australian government refuses to negotiate bilateral investment treaties which contain an ISDS process, and several Latin American nations are cancelling their treaties with developed countries.

2. European and Canadian legal systems are more than capable of handling disputes between investors and governments in cases of serious wrongdoing or breach of contract: ISDS was originally meant to ensure some degree of security for investors in countries where the local legal system was said to be corrupt or incapable of producing fair results. This is not the case in either the EU or Canada – a fact recognized by the European Parliament in its 2011 resolution on the CETA negotiations, which proposes that a state-to-state dispute settlement process is preferable to ISDS. European and Canadian courts have a responsibility to balance corporate interests against the public interest. That balance does not exist in investment treaties or the ISDS process.

3. ISDS forces taxpayers to pay for the public health, environmental and other regulations of their governments: CETA risks removing or weakening the so-called right to regulate from European and Canadian governments. Instead, the investment protections proposed for CETA could require Canadian and EU tax payers to compensate investors when a public law, regulation, policy or program is found to result in a loss or reduction of investment or profit opportunities for the investor. For example, a U.S. energy firm is using investor rights and ISDS in NAFTA to challenge a ban on the environmentally harmful process of hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) for oil and gas in Quebec, demanding $250 million from the Canadian government. In Germany, a Swedish energy firm has taken a proposed phase out of nuclear energy to investor-state arbitration under the rules of the Energy Charter Treaty, asking €3.7 billion in compensation. And in perhaps the most notorious current case, a U.S. cigarette company is using a Hong Kong-Australia bilateral investment treaty to challenge Australia’s right to introduce plain packaging laws – a legitimate public health measure adopted in many countries.

4. The CETA investment chapter ignores the lessons that Canada should have learned since NAFTA, as well as demands for balance from the European Parliament: A leaked December version of the investment chapter in CETA suggests that the European Commission wants Canada to give up on important provisions which Canada has integrated in its post-NAFTA investment treaties to provide some protection for the public interest. For example, if EU proposals are accepted, the treaty would not exempt good faith, non discriminatory measures to protect public health, safety and the environment from prohibitions against so-called indirect expropriation. Similarly, the EU does not want to link the fair and equitable treatment obligation to the customary international law minimum standard of treatment of aliens, as Canada, the United States and an increasing number of other countries now do on a regular basis. The provisions on regulatory expropriation and fair and equitable treatment are two of the most used and abused clauses in investment treaties and NAFTA’s investment chapter. In its 2011 resolution on the EU’s investment policy, the European Parliament called on the Commission to protect the right to regulate. The proposals by the EU in CETA do not do this call justice.

5. Investor-state arbitration is unaccountable and prone to corporate bias: The sharp increase in investor-state disputes over the past five years is fuelled by international law firms and arbitrators, who are making millions by challenging government policy in a shadowy parallel legal system. These vested interests are actively promoting new cases, new investment treaties like CETA, and lobbying against reform of ISDS in the public interest. Arbitrators have far too much leeway to interpret what constitutes fair and equitable treatment or regulatory (indirect) expropriation under the terms of investment treaties. Evidence suggests they are prone to rule expansively in the interests of the complainants (investors), with the result that this encourages more cases in the future.

6. There is scant evidence that ISDS encourages inward or outward investment: While some econometric studies find that investment treaties do attract investment, others find no effect at all. Qualitative research suggests that the treaties are not a decisive factor in whether investors go abroad. Even the Canadian government’s environmental assessments of its recent investment treaties assert they do not lead to added inward investment. Based on a lack of economic benefits, and evidence that investment treaties do pose risks to environmental measures, a Sustainability Impact Assessment of CETA urged the European Union not to include ISDS in the agreement. Like the European Parliament, this independent report for the European Commission suggested a state-to-state dispute process is more appropriate in the EU-Canada context.

The following organizations therefore demand that the EU and Canada cease negotiating investor rights and an investor-state dispute settlement process into the CETA. We will vigorously oppose any transatlantic agreement that compromises our democracies, human and Indigenous rights, and our right to protect our health and the planet. We urge the EU and Canadian governments to follow the lead of the Australian government by stopping the practice of including ISDS in their trade and investment agreements, and to open the door to a broad re-writing of trade and investment policy to balance out corporate interests against the greater public interest.

Signed