All the versions of this article: [English] [français]

Houloul | 13 December 2020

DCFTA: An uncertain economic impact and irreversible consequences on society and sovereignty

by Marco JONVILLE

A version of this article is available in Arabic here

The Comprehensive and Deep Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA), still under negotiation with the European Union, has been so controversial that the European authorities have suggested a name change. Indeed, the economic, social, health and environmental problems and the sovereignty problems posed by the DCFTA have been exposed on multiple occasions (for a summary, see for example https://ftdes.net/note-politique-aleca-tunisie/).

However, the DCFTA continues to be promoted by the European Union (EU), and by certain Tunisian interests, as an essentially political agreement, and as necessary, with positive economic benefits for Tunisia. However, reading the text of the agreement reveals its primarily economic character, through the liberalization of trade and investment. If it is also political, it is because Tunisia will no longer be able to have an economic policy that is independent of the EU.

This is what we will detail in this Policy Brief: we cannot expect a miracle, or even a significant economic improvement with the DCFTA, especially as its irreversible political and social consequences risk preventing development from the country.

The trade balance will continue to deteriorate

Since 2005, Tunisia has been in deficit

The DCFTA is first and foremost a trade agreement, the raison d’être of which is to increase exports and imports. However, this poses a problem at a socially as well as in relation to Tunisia’s current international position.

It is essential to remember that the destruction of jobs caused by new imports and the setting up of European companies will not only represent an economic problem, but also a social one. In fact, they could affect populations already in social difficulty (small businesses, small farmers, etc.) who will not necessarily have the possibility of reintegrating into other sectors of activity.

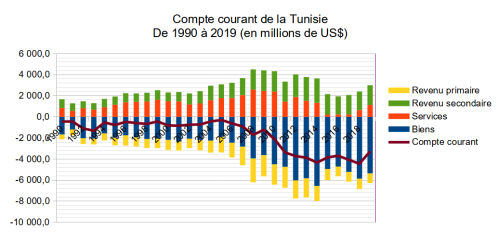

Then, if we look at the evolution of Tunisia’s trade relations (Chart 1), we notice that the trade balance has deteriorated considerably since 2005. This decline is limited by transfers from Tunisians abroad (secondary income) and the balance of services (40% made up of tourism). The deficit is produced by the increase in the external deficit of goods, and of primary income. The deterioration in the balance of goods historically corresponds to the gradual lowering of customs duties on industrial products, in accordance with the Association Agreement with the EU, at the end of the multifiber agreement (which created a more intense international competition in the textile sector), the participation of Asian countries in the World Trade Organization (WTO), and an increase in oil prices, which peaked in 2008 and from 2011 to 2014. The integration of the Tunisia in world trade, accelerated by its entry into the WTO and the Association Agreement in 1995, is currently taking place to its detriment.

Chart 1. Author’s calculations based on IMF balance of payments data

DCFTA would worsen the trade deficit, especially for services, and not improve growth

The more advanced liberalization proposed by the DCFTA will not put back aforesaid the deficit trend. Prospective studies say that a majority of sectors will feel little or a negative effect. Out of 37 sectors of activity, the study by Ecorys (2013), which nevertheless uses a very optimistic model, estimates that in the long term, nine sectors would suffer losses of more than 5% in terms of added value, seven sectors could have gains of more than 5%, and for the remaining 21 the impact would be plus or minus 5%.

Based on these results, it is difficult to understand the 4% growth rate of the economy that the model predicts. The Ofse (2018) study, for its part, measures a negative impact of -1.5% of GDP growth, a stable level of employment and losses in the trade balance.

Beyond the numbers, what all the studies and analyses seem to point to is a neutral impact at best in the long term. The DCFTA will mainly orient production towards certain sectors (less cereals, more olive oil; less textiles, more machines). The costs of adjustment and short-term losses, which Tunisia will have to bear, are not taken into account.

However, if we look at the service sector as predicted by the Ecorys study, we notice that exports would drop significantly in almost all service sub-sectors and imports would increase significantly in all. Thus, if the DCFTA aims primarily to liberalize the services sector, this opening would come at the expense of Tunisia, even according to the long-term forecasts of an optimistic study. The balance of services, already very affected by the drop in tourism since 2014 and again by the corona virus crisis, will no longer be able to limit the trade deficit, or even could become negative as well. The Ecorys (2013) study, like that of Solidar Tunisie (2018), point to opportunities for emerging service sectors in Tunisia. However, according to their own predictions, these same sectors will be the most affected by European competition.

The projections given by these studies are uncertain, but they can give trends: an agricultural sector turned towards the production of oils and fruits for export to the detriment of strategic cereal productions, and a service sector that would become in deficit. The gains would therefore come from the industrial sector, which has already been liberalized by the Association Agreement, and from foreign investments, favored by the DCFTA. What can we really expect from this?

Foreign investments are costly and unprofitable debt

A second major argument used by defenders of the DCFTA is that of the need to adopt this agreement to attract foreign investment (in this case European). These investments would have positive economic spin-offs in terms of growth and jobs that would justify new privileges granted to investors.

Agreements and privileges for investors are costly but not critical to investments

First, the link between the presence of investment facilitation agreements and the amount of foreign investment is unproven. On the contrary, the majority of studies point to an absence of relationship, or only a very slight impact. The latter would be more important in industrialized countries, a category in which Tunisia is not classified. Even without having ratified an investment treaty, Brazil was the world’s third largest recipient of foreign investment between 1990 and 2010.

At the heart of this debate is the question of the privileges that are granted to foreign investors, in particular through the systems of arbitration between investors and States. Tunisia already has 31 bilateral investment treaties which include this system, out of a total of 38 bilateral investment treaties currently in force. But DCFTA would extend this system to the whole of the EU and make it even more difficult to question, since there would be no deadline for this treaty and it would be more difficult to renegotiate. These treaties allow foreign investors to seek reparations from the state if they believe that regulation, even in the public interest, has harmed their expected profits. Two frequently cited cases are the example of the company Vattenfall which requested 6 billion euros from Germany following its decision to exit nuclear power, or the company Veolia which requested 175 million euros from Egypt following its decision to increase the minimum wage. Foreign companies can also use the threat of arbitration to change laws, as in France regarding a law on hydrocarbons. South Africa, the first recipient of FDI in Africa, has decided to end its investment treaties which include arbitration, faced with its costs and after noticing that a lot of investments came from countries with which she didn’t agree. However, the FDI inflows it receives have not declined. To protect itself, Tunisia should follow a similar path.

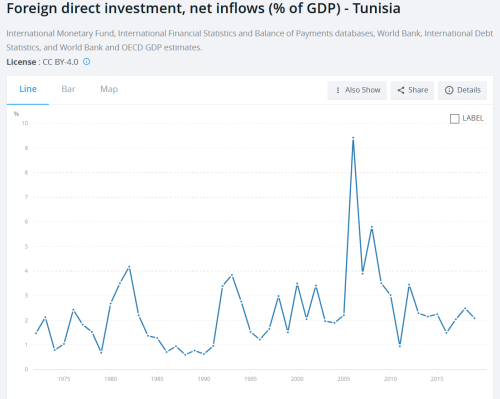

The main policy to attract FDI (Foreign Direct Investments) to Tunisia has been the offshore regime, the results of which are controversial. This regime has given great advantages to investors who want to take advantage of the Tunisian workforce to re-export their products. DCFTA would give them more. However, when we look at FDI flows, we do not notice a striking influence: there is no surge in investments following Law 72 or following the Association Agreement of 1995. On average, FDI has been between 1 and 4% of GDP since 1970 with a slight upward trend (Figure 2).

Chart 2 – Net inflow of inward FDI, as a percentage of GDP. Source: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/BX.KLT.DINV.WD.GD.ZS?locations=TN

Investments must be controlled and directed to enable development

On the other hand, foreign investment does not mean an automatic increase in the welfare and employment of the country. If they exist, the additional investments that could be made with the DCFTA would target the Tunisian market more directly, since the offshore regime already makes it possible to target exports very freely. For example, investments in the retail sectors would strengthen supermarkets, to the detriment of small businesses, leading to greater concentration. We can therefore expect a net loss of jobs in this sector.

Thus, FDI would lead to more competition with Tunisian companies (in addition to additional imports), but above all, the DCFTA will not accompany these investments as guarantees to improve the Tunisian economic fabric itself. The agreement prohibits Tunisia from setting conditions for foreign investment, such as technology transfer, the employment of national executives, having recourse to a minimum of Tunisian suppliers, etc. However, to be truly useful in building a more prosperous economy, FDI must be directed towards sectors for which it is useful, and benefit local businesses, as part of a government strategy to develop and improve the productivity of some sectors. It is particularly thanks to this type of strategy that the newly industrialized Asian countries have successfully “caught up”. This implies using the technologies acquired through the investments by disseminating them to the rest of the economy: it is this diffusion and “domestic integration” that are essential (Rodrick, 2018).

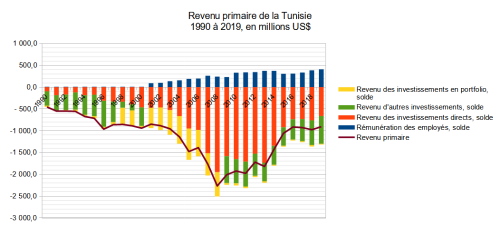

FDI: first a debt

FDI cannot be seen as a sustainable solution, especially under these conditions. FDI represents a debt: it is inflows of foreign capital, which must be remunerated. Thus, if we look at the primary income, we notice that Tunisia must pay a significant sum to foreign investors for their remuneration, especially between 2009 and 2013 (deficit of more than 1.5 billion dollars each year), following the Significant FDI which was recorded between 2005 and 2010. With the fall in FDI, this deficit has also fallen. For some countries like South Africa, FDI remunerations thus represent the major part of their trade deficit, so the country owes a debt to the rest of the world because of FDI.

FDI can also represent large direct losses: between 2000 and 2012, Tunisia received 3.547 billion TND of FDI from the United Kingdom, but 7.08 billion TND were repatriated, a net loss of 3.533 billion TND. Thus, it is necessary to control this debt and what it brings to the development of the country.

Chart 3 – Author’s calculations based on IMF data. “Income from other investments” refers exclusively to interest paid on government loans abroad.

European standards promote the interests of dominant players and aggravate existing problems

A third consequence of the DCFTA would be to adopt European standards. Defenders of the agreement say it would bring Tunisia to better standards, force it to carry out stalled reforms and fight corruption, making the market more efficient.

Intensified competition, corruption and the social crisis still there

The majority of European standards mainly focus on what the EU considers to be good competition. However, this is not always favorable to consumers or to the economy, as the Tunisian Observatory of the Economy reminds us about the energy sector. We can fear a grabbing of Tunisian resources, and a privatization of energy distribution for the benefit of European operators, without positive consequences for consumers but net job losses to the detriment of STEG. Competition in public procurement would threaten all Tunisian companies that benefit from Tunisian markets (15 to 20% of GDP), especially small businesses, by putting them in direct competition with European companies. Competition standards represent a certain economic ideology which is partly responsible for the lasting social crisis in Europe – the yellow vests movement in France is one of its manifestations. The reign of competition, the neoliberal system and the domination of large companies has led to the precariousness of a large part of the population and to a social crisis which reigns in Europe. European standards do not prevent agreements between actors and corruption scandals, including in public procurement. Corruption must be addressed directly and systematically. Market rules could just as easily be circumvented as current rules.

Standards for the benefit of large European and Tunisian companies, a larger informal market

The standards also concern production standards, product calibration, etc. The latter push for the standardization of products, and a certain mode of production, especially in the agricultural sector. While some would improve safety and compliance with environmental standards, it is not known whether they will fit the Tunisian context. European standards will favor large Tunisian companies, which will know how to apply them easily or already apply them for exporting, or European companies which will be able to enter the market more easily. Europeans will remain better at applying their own standards, since they will not have to adjust. We can therefore expect losses for Tunisian companies, some of which will have to close, as well as an increase in the informal market, which is unable to apply the required standards.

Imposing reforms from outside and against the people is not a solution

On the other hand, defenders of the DCFTA argue that the deal would help advance stalled reforms in Tunisia. They therefore adopt a strategy that imposes reforms that many Tunisians refuse. The application of European standards provokes strong resentment against the European Union in many states of the EU itself. In Tunisia, the anti social reforms imposed by the IMF also provoke strong resistance movements among the population. DCFTA takes the logic of IMF reforms one step further by establishing the rule of competition and the privatization of many sectors. From a strictly political point of view, the reforms must be the result of the democratic process and not come from an international agreement on which citizens will not have had the opportunity to express themselves, or who do not offer only one alternative to deputies, that of accepting or rejecting it en bloc. From an economic point of view, the effectiveness of these reforms for economic development is highly questionable and frequently contested by economists and the population.

Restricted and limited development opportunities by DCFTA, a frozen role in global value chains

Alternatives exist but agreements like the DCFTA restrict them

According to its supporters, the standards and reforms that accompany the DCFTA would be imperative to modernize Tunisia and integrate it into international competition. There would be only one way to grow the economy, the one they advocate. The absurdity of such a claim, crushing the reality of human complexity, is found in the belief in an economic “science” that holds the truth, while economics is fundamentally social, as it arises from human interactions. The alternatives and the diversity of positions still exist, and few countries have been able to develop by following the recipes prescribed by the IMF or the World Bank. China or South Korea have experienced expansions without following them. These countries imposed capital controls, and protected and invested in certain industries. Such policies would be made completely impossible by the DCFTA. In a recent study, Dühnaupt and Herr (2020) show how this type of agreement makes it very difficult, if not impossible, to implement an industrial policy that can benefit a country in the South. In addition, by being integrated into world trade and its value chains, many countries are restricted to certain tasks and do not benefit from either economic or social improvements.

DCFTA is not modern and will not allow Tunisia to follow its sovereign development

More concretely, this agreement ties the hands of Tunisia in the exercise of its sovereign choices. It will automatically have to follow European standards without having the opportunity to discuss them. Even if these standards are positive, they must come from Tunisia itself in order to adapt them to the economic and social situation of the country. In terms of integration into international trade, the majority of companies wishing to export already meet international standards. During the discussions on the DCFTA, the problems that emerge are more internal issues: the lack of visas and the non-convertibility of the dinar seem to be the main problems for exports of services.

Moreover, what modernization are we talking about? The methods of modernizing agriculture used since the 1970s have largely destroyed the soil and the resistance of ecosystems and crops to shocks (climatic, epidemics, etc.). In Europe, competition and aid from the CAP (Common Agricultural Policy) mean that farmers would not survive without European aid. Modernization of the economy through higher technologies? We have shown above that the link with investment is not automatic. It is therefore impossible to expect automatic fallout from such an agreement.

Alternatives:

Tunisia’s economic standards and choices must remain sovereign. This agreement prevents it. Tunisia would agree to apply a recipe that the EU has prepared for it (and intended for all Mediterranean countries), and on which the negotiating margins are minimal. Thus, with the DCFTA, Tunisia could no longer choose its norms and standards: it would accept its status as a satellite of the European Union, automatically following its standards. It is in this sense that we can affirm that the DCFTA is a neocolonial agreement. Yes, the economic and social consequences are to be feared, especially in the short term and in a situation where the Tunisian economy is unable to adapt to such a change. And in economics, it has been shown empirically that large short-term losses also have lasting consequences. Yes, the agreement is neocolonial in the sense that it would give more power and income to European firms which already have great advantages under the offshore regime. It would thus increase Tunisia’s debt and trade deficit. But above all, it is neocolonial because it allows the EU to ensure that Tunisia, and the Mediterranean countries which will sign another ALECA, remain in its sphere of influence and control.

Far from saving Tunisia, DCFTA will mortgage its future at the goodwill of its external creditors. A serious economic analysis of the consequences of the DCFTA hardly reveals a positive impact. On the contrary, the reductions in the possibilities of carrying out active and sovereign economic development policies, as well as the impacts on the economic and social rights of Tunisians, food sovereignty, access to medicines and inequalities have been proven.

A real development strategy must be based on political and economic sovereignty, control of capital and its use, social, economic and environmental justice.

Recommendations:

- Refuse the European offer from DCFTA.

- Revise bilateral investment treaties as they expire to remove the investor-state arbitration clause and unfair privileges granted to investors.

- Gradually challenge the offshore system by integrating it into the local economy.

- Pursue capital controls, demanding systematic technology transfers and the employment of national executives from companies based in Tunisia.

- Develop a different mode of development for Tunisia, on the basis of demanding social and environmental standards, and choices concerning sectors to be protected in order to develop them or because these are strategic and essential productions for the country (cereals, information technologies…).

- If deemed necessary, propose a real partnership agreement to the EU, on the basis of identified Tunisian needs (to carry out exchanges of skills, promote social programs, specific technology transfers, allow imports that Tunisia does not is not intended to produce, promote selected exports…).

Bibliography

- Ayeb H. (2018), « Sortir de l’ALECA et de l’ensemble du système alimentaire mondial : Pour une nouvelle politique agricole et alimentaire souveraine qui rompt définitivement avec la dépendance alimentaire et les marchés internationaux », https://osae-marsad.org/2018/12/31/sortir-de-l-aleca-pour-une-nouvelle-politique-agricole-et-alimentaire-souveraine/

- Bedoui A., Abdelmalek A., Saadaoui Z. (à paraître), Étude de l’impact attendu de l’ALECA sur les micro-entreprises dans les secteurs du commerce et des services en Tunisie, FTDES

- Bedoui A. et Mokadem M. (2016), Evaluation du Partenariat entre l’UE et la Tunisie, Rosa Luxemburg Stiftung

- Ben Rouine C. et Chandoul J. (2019), ALECA et agriculture : Au-delà des barrières tarifaires, Observatoire Tunisien de l’Economie, http://www.economie-tunisie.org/fr/observatoire/aleca-et-agriculture-au-dela-des-barri%C3%A8res-tarifaires

- Bonnefoy V. et Jonville M. (2018), « Négociations UE-Tunisie : Libérer les échanges sans échanger les libertés ?», Forum Tunisien pour les Droits Économiques et Sociaux, https://ftdes.net/ue-tunisie/

- Brada J., Drabek Z., Iwasaki I. (2020) “Does investor protection increase foreign direct investment? A Meta-analysis”, Journal of Economic Surveys (2020), Vol. 00, No. 0, pp. 1–36

- Dünhaupt P. et Herr H. (2020), Catching Up in a Time of Constraints: Industrial Policy Under World Trade Organization Rules, Free Trade Agreements and Bilateral Investment Agreements, Friedrich Ebert Stiftung

- Ecorys (2013), Trade Sustainability Impact Assessment in support of negotiations of a DCFTA between the EU and Tunisia, Final Report.

- FTDES, CNCD 11.11.11, EuroMed Droits, ITPC MENA, TNI (2018), Note Politique ALECA UE-Tunisie, https://ftdes.net/note-politique-aleca-tunisie/

- ITCEQ (2016), Evaluation de l’impact de la libéralisation des services dans le cadre de l’Accord de Libre Échange Complet et Approfondi (ALECA) entre la Tunisie et l’UE, Etude n°04/2016

- ITPC (2017), Évaluation du cadre légal en matière de propriété intellectuelle et impact sur l’accès aux médicaments (Egypte, Maroc, Tunisie), International Treatment and Preparedness Coalition,

- Jeanne d’Othée N. (2020), Pour un partenariat méditerranéen en faveur du développement durable, Points Sud #19, CNCD 11.11.11

- Jonville M. (2018), Perceptions de l’Accord de Libre Échange Complet et Approfondi (ALECA) : Étude des attentes et conséquences économiques et sociales en Tunisie, Forum Tunisien pour les Droits Economiques et Sociaux, https://ftdes.net/rapports/etude.aleca.pdf

- Louati I. (2019), ALECA, Production d’électricité et Energies renouvelables : Quel avenir pour la STEG et la transition énergétique en Tunisie ? Observatoire Tunisien de l’Economie, http://www.economie-tunisie.org/fr/observatoire/ALECA-Production-electricite-Energies-renouvelables-Steg

- Louati I. et Jegham O. (2020), Droits de propriété intellectuelle et ALECA : une menace pour l’accès aux médicaments ? Observatoire Tunisien de l’Economie, http://www.economie-tunisie.org/fr/observatoire/droits-de-propriete-intellectuelle-ALECA

- Mahjoub A. et Saadaoui Z. (2015), Impact de l’accord de libre-échange complet et approfondi sur les droits économiques et sociaux en Tunisie, Réseau Euromed pour les Droits de l’Homme Tunisie

- Morosini F., Sanchez M. (2017), “Reconceptualizing international investment law from the Global South – an introduction” dans Reconceptualizing International Investment Law from the Global South, Fabio Morosini and Michelle Ratton Sanchez (eds.), New York: Cambridge University Press, pp. 1–46.

- Ofse (2018), The economic and social effects of the EU Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA) with Tunisia, Austrian Foundation for Development Research

- Poulsen L. (2010), “The importance of BITs for foreign direct investment and political risk insurance: revisiting the evidence” dans Yearbook on International Investment Law and Policy 2009/2010, New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 539 –574.

- Riahi L. (2014), « Coûts des investissements directs étrangers », Observatoire Tunisien de l’Economie, http://www.economie-tunisie.org/fr/observatoire/visualeconomics/couts-ide-tunisie

- Robert D., Canonne A., Dadci L. (2016), « UE-Tunisie : diktat de la libéralisation commerciale ou partenariat authentique ? », Association Internationale des Techniciens Experts et Chercheurs

- Rodrik D. (2018), “New Technologies, Global Value Chains, and the Developing Economies”, Pathways for Prosperity Commission Background Paper Series; no. 1.

- Summers L. (2014), “Reflections on the new ‘Secular Stagnation hypothesis’”, https://voxeu.org/article/larry-summers-secular-stagnation